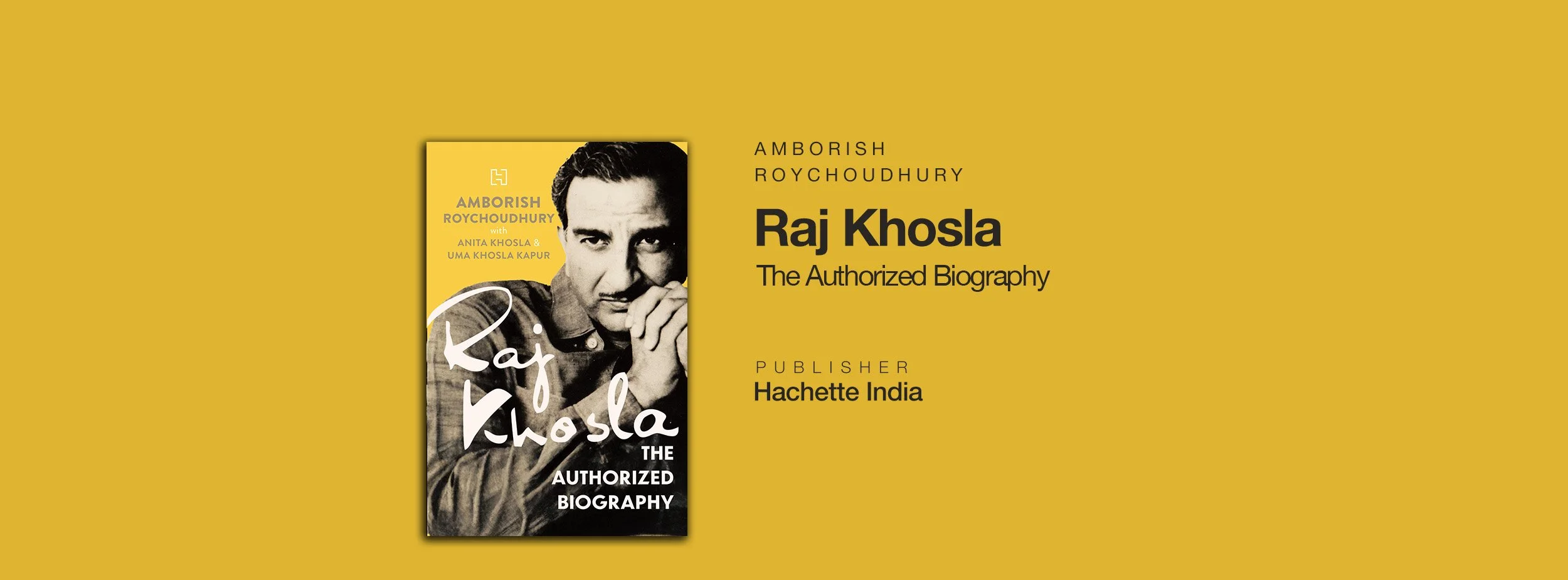

It may have been a coincidence that the autobiography of Raj Khosla should be released during the centenary of Guru Dutt and yet, the book is more than a biography. It is actually a history of Hindi Cinema, the classic years. It is to the credit of the author, Amborish Roychoudhury, that he has not only written about a man who dominated Hindi cinema, Bollywood as it is popularly called, without meeting him and filling every nook and crevice of the storyline with rare anecdotes which leave you in a state of awe.

As the author says in his introduction, Raj Khosla has just remained a footnote in the books and stories on Guru Dutt and after reading the book I felt that Amborish had actually done great justice to the man, whose death was reported in a few inches muscled in the newspapers, but who was actually a Bollywood great. He was. Be it CID or Hai Apna Dil from Solva Saal, it was Raj Khosla all the way. Once you have gone through the book you are left wondering why Raj Khosla has not been celebrated like his contemporaries.

I cannot but applaud Amborish for putting together the life and times of Raj Khosla by doing his own research, going through heaps of documents, books, and possibly the only interview recorded and telecast (documentary on Guru Dutt by Nasreen Munni Kabir), a team of researchers who supported his endeavour (all of whom have been gracefully acknowledged), and his meetings with a long list of people from the industry, including Asha ji who patiently went through Khosla’s films one by one. To that add his co-authors, Raj Khosla’s daughters Anita Khosla and Uma Kapur Khosla, who provided the insights and Raj Khosla the man.

What we have in hand is a great tribute to a great filmmaker who, for some odd reasons, may have been lost in the decibel level of the new generation. It is indeed sad that it took almost 35 years after his death for a book to be written on this giant of Hindi cinema who had presented us with CID to Woh Kaun Thi to Main Tulsi Tere Angan Ki, in a career spanning over three decades.

In the book suddenly the entire world of the 50s to 80s comes alive. We have the story of a man who wanted to be a singer, be another K. L. Saigal, goes on to get his first job in films as a double for a heroine for Rs 75, and finally goes on to make blockbusters filled with songs, one of which being the timeless Lag Jaa Gale, which Lata ji had listed as one of her six best songs (a song which was initially rejected, then pushed by Manoj Kumar to be heard again, when he not only lamented his earlier decision but even slapped himself with his shoes to atone for having rejected it earlier). They are still favourites on YouTube.

The influence of Guru Dutt, who had in many ways been his teacher and mentor, has been very well outlined in the book, and rightfully so. Khosla, who was left heartbroken at the sudden passing away of Guru Dutt, had even dedicated his film Anita to his master. His beginnings as an assistant to Guru Dutt are well encapsulated in the following story:

“When I began briefing Geeta Bali she stopped and said, ‘don’t explain anything to me, just sing the song’ (Tadbeer Se Bigdi). The young man rarely needed more encouragement to break into a song. He performed the lines in his own inimitable style and Geeta smiled.”

Thirty years in an industry—any industry—is a long, long time and, as in life, nothing always goes the way you want it. Khosla’s life too was full of highs and lows. He had a major setback after a dream run of his first set of films and yet he stood up and finally had a score of 23 films. It was not just the films, it was also the songs in the films. And the people he made. When a 20-year-old Mahesh Bhatt tricked his way past the burly watchman of Mehboob Studios and met Khosla, he was asked, “Do you know anything about filmmaking?” When Bhatt replied in the negative, he grinned and said, “Ah! Zero is a great place to start.” The story, told by Bhatt himself in the foreword to the book, speaks so much about a man’s leadership qualities.

In an interview with Nasreen Munni Kabir, Waheeda Rehman had remarked: “Raj Khosla was a very good director. He filmed songs very well… he was a very nice person to spend time with….”

The book is laced with many nuggets which, to me, came as a bonus. Bhappi Sonie, who directed Janwar and Brahmachari, worked as a ticket checker at CSMT station and he would be relieved by Shammi Kapoor who would wear his uniform and do his job while Sonie went and saw a movie at Capitol. Upon return, they would switch and Shammi would go and see the film in the next show! That Prem Chopra worked as supervisor in the circulation department of Times of India to make both ends meet and frequented Gaylord restaurant, when he was offered a small role as they wanted a face that was not recognizable!

Khosla’s oeuvre, that covers anything between crime thrillers to family dramas, had a special place for women. He was immensely affected by the women in his life—his mother, his wife, his five daughters—and they impacted him deeply. This is even more true of his treatment of women in Main Tulsi Tere Angan Ki.

The book has come late, but I am sure it will help film buffs and film historians, generations who have been in awe of that “classic” period of Hindi cinema, to come together and celebrate the life and times of Raj Khosla.