The bond between mothers and daughters is never easy, despite all the platitudes about the woman who carried you in her womb for nine months and stayed heartbeat to heartbeat. Mothers and daughters often share an edgy, competitive relationship that surfaces at the oddest times. Arundhati Roy’s memoir of her mother brings this out with striking clarity. Her mother was the one who “set hooks floating through her blood” and treated her worse than anyone knew. This accounted for their long estrangement despite occasional brittle reunions — and for the fact that Roy refers to her mother as “Mrs Roy” throughout, rather than Mummy or Ma, in her attempt to “undaughter” herself.

It is a September book — Mary Roy passed away in that autumn month, and the Roy siblings flew down to Kerala because their grief at something they had expected for years was nonetheless overwhelming, especially Arundhati’s. This, her brother wondered at, given the way Mary Roy had treated her daughter. She was merciless Arundhati often said – to her children and to dogs.

Life had stacked the odds against Mary Roy — an alcoholic husband whom she left when Arundhati was two; the exquisite art of failure, her daughter called it later - only to find herself with no money and no place to go except her maternal grandfather’s house in Ooty. That move triggered a property dispute between Mary Roy and her Rhodes Scholar elder brother, eventually leading to her landmark legal victory on equal property rights for women. Seething underneath was her rage against her husband, who came to symbolise all the men in her life — a rage she visited on both her children and which her daughter inherited, so that the Bengali “nothing man” became the writer’s infamous father (who nonetheless left happy memories for her brother).

They led a fugitive life until they returned to Mary Roy’s birthplace, Ayemenem — familiar to all readers of The God of Small Things. Roy moves back and forth between past and present, revealing that her novel was in fact far from fiction, and that Mary Roy read it anxiously to see if any family secrets had been spilt.

Ayemenem — the exotic beauty of Kerala and the green river reflecting the yellow broken moon — brings Arundhati Roy’s language to the fore, its lyricism masking the edgy content and her mother’s “fold-and-slide” life in the opening chapters of the book.

Mary Roy’s precarious health and her brilliance as an academic — which allowed her to “mother” all her students barring her own children — gradually emerge, an escape from the rage and grief that constantly burned within her. In an atmosphere riddled with strife, it was a fight for survival. This is nothing unusual to those who know families riddled, like cheese, with land issues and politics — made more complex by the fact that this was an educated, cosmopolitan family still floundering in patriarchy.

Like her mother, who married a Bengali to escape her abusive father and Syrian Christian family, Arundhati fled to Delhi to find a new life as an architect, at a time when the world was shifting its perspective. Mercurial mother, lack of love and the shifting ground beneath her feet combined to make Roy the novelist she became, steeled by the backbone she had inherited. Confronting both was a parallel of sorts: Mary Roy and the new India had to be resisted or embraced, if Arundhati was to be true to herself. She wrote: “For my part, I wanted to test myself… Could I write about irrigation, agriculture, displacement, and drainage the way I wrote about love and death?”

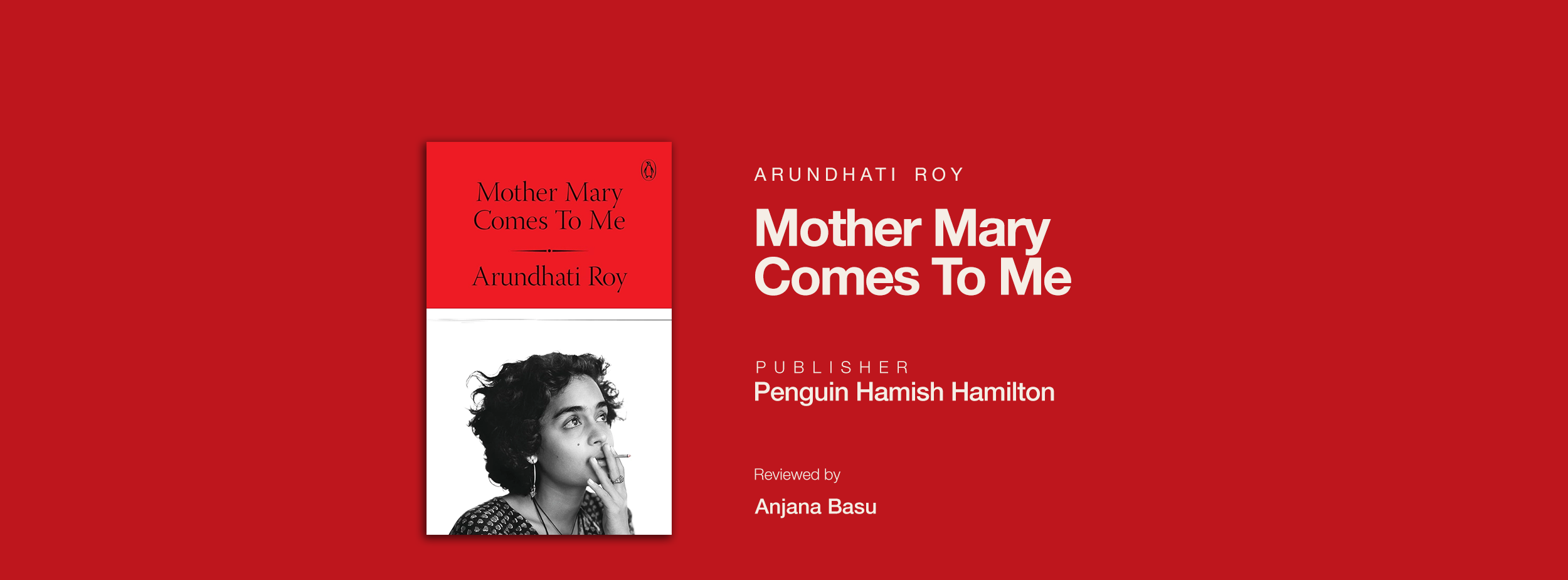

While few people knew Mary Roy beyond educators who applauded her, most people thought they knew Arundhati Roy. Yet Mother Mary Comes to Me is not just a memoir of a mother; it is everything you wanted to know about Arundhati Roy but didn’t know what to ask – sex, cigarette smoke and all. She avoided meeting her mother for years, until she finally decided to bridge the gap. She also eventually met her father, in a rather hilarious — or perhaps satiric — encounter that took the ‘mickey’ out of him and made her wonder how her parents had managed to stay married for five years.

Many daughters have complicated relationships with their mothers, but not all of them write memoirs that reflect their mothers’ dark side so completely. Even though there was always an undercurrent of emotional blackmail in Mary’s ever-present threat of imminent death triggered by asthma, in a sense, she was the architect of her daughter’s brilliance — which may account for the writer’s unexpected grief at Mary Roy’s death. Mother Mary gave her words of wisdom, after all.

One would have hoped to find an image of Mary Roy on the cover along with Arundhati, but then…